Protest as a Catalyst for Change

These days my writing life is filled with magic, myths, adventure, and quests-style novel writing. But in my past academic life, my writing was all non-fiction, essays of a wide variety.

As I look back on some of the short essays I penned, I realized they have significant relevance still today and thought I’d share them you.

One such essay from Dr. Goss’s English 102 class is entitled:

Protest as a Catalyst for Change in the 1960s Through Speech, Written Word, and Song

One of the greatest catalysts of change is protest, and in American History, the 1960s, more than any other age, reveals the power of protest and its impact on the events of this decade.

The Declaration of Independence makes the claim “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

The Declaration of Independence makes the claim “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

In the 1960s, economic, social, and political conditions in America caused more people to question traditional practices about how people were regarded. Americans witnessed the rise of feminism and the counterculture, but also the painful birth of civil and gay rights, and the student free speech, anti-Vietnam, and environmental movements. At times, America seemed in chaos.

As Joel P. Rhodes observes, “It was a time of conflict between war and peace, national interests, and individuals” rights, social justice, and racism, young and old, straight and freak, custodial liberalism, and participatory democracy, us and them.”

And it was a combination of these new, radical, and subversive events and trends of the period that inspired and motivated some individuals to speak out on the injustice and inequality they observed or experience firsthand, and protest in songs, speech, and in writing, that contributed to these changes.

American music has left its mark and in the 1960’s many protest songs were written to inspire and convey what was in the hearts and minds of the majority.

Notable songs such as:

“Turn! Turn! Turn!” from the album, The Bitter and the Sweet written by Pete Seeger and “Give Peace a Chance” by John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band in 1969.

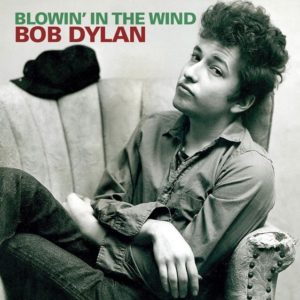

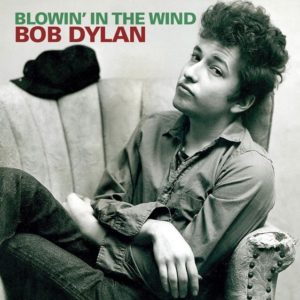

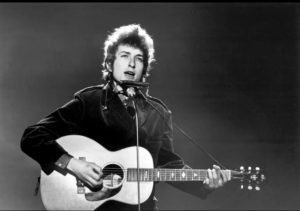

These songs were extremely moving, but one such unlikely singer and songwriter would go on to be identified as the top protest songwriter of his day. Musician Bob Dylan – and three of his songs all made it to the Top Ten most-recognized protest songs of the 1960s:

“With God on our Side,” “Masters of War” and most importantly “Blowin’ in the Wind”.

“Blowin’ in the Wind” (his most famous song at the time) was first played at Gerde’s Folk City on April 16, 1962. In this song, Dylan asks nine timeless questions concerning human rights violations, oppression, and war.

1) “How many roads must a man walk down/ Before you call him a man?”

This question references racism felt in society after desegregation and the discrimination of those who are not white and how much one has to experience before one gains respect. This question may also refer to protestors walking on the streets of America attempting to gain respect and equality.

2) “Yes, ‘n’ how many seas must a white dove sail/Before she sleeps in the sand?”

This question has the dove representing peace, and the color white purity, while sleeping in the sand signifies death. There can be no peace in the world until all the fighting stops because there is no place to sleep in the sand due to the continual fighting on the beaches around the globe.

This line may also be viewed as a biblical allusion. Genesis 8:8 says Noah sent a dove to find calm waters, but the dove found none, leaving it unable to rest in the sand. It’s common knowledge that the flood was caused by man’s sin. At the time the flood was still upon the earth with no accessible land and consequently gave the dove no rest.

3) “Yes, ‘n’ how many times must the cannon balls fly/Before they’re forever banned?”

Death and destruction may temporarily stop hostilities, but do not create a positive outcome or resolution. How many lives will be destroyed by weapons before man stops and a more peaceful solution is employed?

4) “How many years can a mountain exist/Before it’s washed to the sea?”

Corporations and the military machine can exist for a finite period of time, but even such things eventually succumb to time.

5) “Yes, ‘n’ how many years can some people exist/Before they’re allowed to be free?”

History shows that slavery and other forms of oppression all meet with eventual resistance to the point they become a non-viable economic investment.

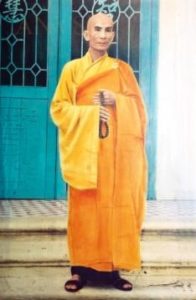

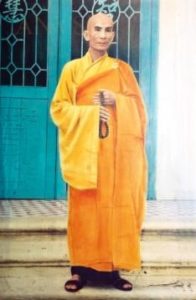

6) “Yes, ‘n’ how many times can a man turn his head, /Pretending he just doesn’t see?”

A horse can be made to wear blinders so it can walk on city streets without certain images causing stress that prevents it from working. Some individuals opposed to religious discrimination and the Vietnam War protest such things through self-immolation. On June 11, 1963, Thich Quang Duc, a Buddhist monk from the Link-Mu Pagoda in Hue, Vietnam, burned himself to death at a busy intersection in downtown Saigon, Vietnam. President Kennedy had this picture on his desk the next day.

7) “How many times must a man look up/Before he can see the sky?”

Relief comes in many forms. Slaves and the underclass throughout history have been forbidden from looking up at the faces of the upper class and rulers. All men and women are equal and shall be able to look upon one another’s faces.

8) “Yes, ‘n’ how many ears must one man have/Before he can hear people cry?”

Birth, life, and death are all experiences everyone shares being part of the human condition. There is only so much sorrow, grief, and misery any one person can be exposed to before the right person in a position of power, is made aware of such conditions and is able to change them.

9) “Yes, ‘n’ how many deaths will it take till he knows/That too many people have died?”

This question references the popular sentiment regarding the war in Vietnam, with President Kennedy being the “He.”

Dylan is brilliant in his use of rhetorical and literary techniques to convey his message. His song is simple; three stanzas each containing three rhetorical questions, that he answers with the same phrase for listeners to reach the clear conclusions. Dylan shows these topics have already been raised and questioned by his use of the words “how many. . . “and suggests additional questions are not needed to resolve the condition or circumstances. This shows knowledge and enlightenment are right in front of us, but just like the wind, we cannot see them.

Ironically, at this performance Dylan introduced the song, saying it was not written as a protest song. Dylan revealed more about the mechanics of writing the song in the Los Angeles Times:

“I wrote ‘Blowin’ in the Winds’ in ten minutes, just put words to an old spiritual, probably something I learned from Carter Family records. That’s the folk tradition. You use what’s been handed down” – and, of course, pass it on.”

This song partially derived its melody from the traditional slave song “No More Auction Block,” while its lyrics questioned the social and political status quo. Before playing it, he announced, “This here ain’t no protest song or anything like that’ cause I don’t write no protest songs.” During this first performance, Dylan could not read some of his handwriting and made up some of the lyrics as he went along. This song is applied to many different situations because it is not specific or connected with any one particular conflict. It is a simple, universal proclamation for everyone to learn from their own mistakes and a call for freedom.

This song does an excellent job of bringing together anti-war protestors. In June 1962, the song was published in Sing Out! accompanied by Dylan’s comments:

“There ain’t too much I can say about this song except that the answers is blowing in the wind. It ain’t in no book or movie or TV show or discussion groups. Man, it’s in the wind and it’s blowing in the wind. Too many of these hip people are telling me where the answer is but oh I won’t believe that. I still say it’s in the wind and just like a restless piece of paper isnt’s got to come down some . . . But the only trouble is that no one picks up the answer when it comes down so not too many people get to see and know . . . and then flies away I still say that some of the biggest criminals are those that turn their beads away when they see wrong and know it’s wrong. I’m only 21 years old and I know that there’s been too many. . . You people over 21, you’re older and smarter.”

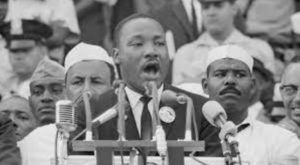

Another excellent example of a well-written and delivered protest speech is by the Novel Peace Prize Recipient Baptist Minister, Dr. Martin Luthor King Jr., who delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech on August 28, 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington DC.

His message of change through non-violence, employed rhetorical methods, including repetition, identification, and persuasion to inspire over 250,000 listeners in among the most inspiring and moving speeches of all ages. It is easy to discern why his powerful message resonated with so many people of his time and still profoundly affects so many lives to this day.

Dr. King’s attempts to identify and unite himself with his listeners’ and he begins by providing a historical background that sounds similar to Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address of November 19, 1863.

He chronicles the struggles of Black Americans in White Society and current circumstances tugging at the heartstrings of the mass of individuals listening to him which need to be addressed and corrected. He explains his goals and proposes a solution. Dr. King enhances his speech by continued use of repetition and metaphors, and to summarize his main goals. Finally, he closes with “Free at last! Free at last? Thank God Almighty, we are free at last?”

At the time of the speech, then-President Kennedy was concerned that a small crowd could undermine his civil-rights efforts. Ironically, this speech was part of a larger event designated to put greater pressure on the President and his administration to advance civil rights legislation in Congress. Less than a year after the speech, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson.

The 1960s was a time of change both good and bad, unlike any seen and experienced beforehand or after. The best came about not by violence and aggression but through the peaceful expression of protest by individuals such as Bob Dylan and Dr Martin Luther King Jr. that helped shape individuals, our society and nation by placing us all on a better path of tolerance and respect for ourselves and others that we are still experience today.

When you consider what’s going on in the world now – overzealous, overcontrolling, and out-of-control leaders, lockdowns don’t benefit the masses, BLM Riots in cities across America, Yellow Jackets in the street across France, burning down the PM’s house in Sri Lanka, and the war in Ukraine, isn’t the best direction to bring and deliver peace.

The Beatles sang all you need is love, and John Lennon said give peace a chance.

But the world could use the Bob Dylans and Martin Luther King Jr’s of today, like the young poet Amanda Gorman, or American singer, songwriter, musician, and author Josh Ritter, able to express and voice our shared outrage, our shared dismay, and our shared focus to bring and deliver a world where peaceful protests achieve a world of love, a world of peace, all because we gave love and peace a chance over war and strife.

What say you?

Drop me a line, I would love to hear from you!

All images, text, materials, code displayed on this website are Copyright © by J.W. Zarek. Illustration created by Peter Johnston. All Rights Reserved.

Author Website design by Rocket Expansion – © 2021

Author of Non-fiction, Fantasy

and Graphic Novels